What is your favorite Sunday lunch memory? Ask anyone from the south of India and, age-no-bar, their answer would be this. Either a sambar, rasam, or a spicy kuzhambu - all tamarind-based broths- a crispy potato curry, apalams, rice, curd, and the entire family gathering for lunch.

For me, as for many of you, that memory is special as Sundays were when our parents would finally set aside work. My dad, cleaning the house, a duster and Colin’s spray in hand. My mum, who taught me the art of one-pot cooking much before it became popular, actually spending more than 30 minutes in the kitchen. Ilayaraja or Kishore Kumar tracks on loop in the background.

My parents’ Sunday memories three decades earlier involved different chores and different songs, but that tamarind broth-potato curry-rice meal has remained a constant fixture.

So, last weekend, when my husband and I cooked that same meal for my parents, I couldn’t help but wonder where the humble tamarind broth came from, and what makes it that magical potion that at once, brings people together in the fondness of nostalgia.

We made a vatthal kuzhambu. The original recipe (by which I mean the grandmother recipe delivered down generations) uses dried vegetables (vatthal), onions, tomatoes and tamarind.

Ours, however, was the 2021 version. Without the luxuries of a private terrace or courtyard with plenty of sunlight to dry the vegetables, we instead combined my husband’s Sunday kuzhambu memories and mine, added a pinch of my mother’s recipes and his, and were guided not by written-down recipes, but the wisdom of our ancestors’ kitchens.

A TANGY ORIGIN STORY

The most popular of the tamarind broth-based dishes, the rasam, likely originated in 16th century Madurai, a temple town in the southern state of Tamil Nadu.

But, let’s travel further back into time, with a more basic question. Where did the tamarind come from? Did the tamarind broth belong in royal kitchens or in the humble huts of the pastoral people? Was it always served in the form which we know and so relish, and how has it evolved?

AN AFRICAN CONNECTION

South Indian food has been enriched by a variety of influences, and among its earliest was an African influence.

The renowned food writer K.T. Achaya writes in his seminal 1994 book, Indian Food, A Historical Companion, that southern India had a connection with Africa through Gujarat, when the seas were at a considerably lower level than today and a land bridge existed between the two regions.

While that African influence was seen in the similarity of tools and animal remains found in either region, it is also reflected in old food finds from the time - of grains such as ragi, bajra, and jowar and vegetables and fruits such as the okra, some gourds, and, our hero, the tamarind.

However, various research on the archeological finds of the region, as well as descriptions of food in Tamil and Kannada literature, say different stories of the humble tamarind broth’s origins.

LIT RECIPES, AND A MEATY DIVERSION

Ancient Tamil literature portrays foods in occupational and regional terms - some specific to mountain folk, others to pastoral and fisherfolk. Several works, in varying degrees of detail, also exalt meat - from red iguana meat to flesh of the fowl.

“Pre-Aryan southerners had no inhibitions of eating flesh,” Achaya writes. But even after the Aryans reach south India, the famous Brahmin priest Kapilar of the Sangam age, “speaks with relish, and without the fear of social ostracism” of the use of meat and drink.

The Tamil people had four names for beef and 15 names of the domestic pig, indicating their wide use.

Perumpanuru, a text from the Third Sangam Age in the 3rd or 4th century AD, talks of an adult bull being slaughtered in the open, and the Tamil word for fish, meen, even entered Sanskrit.

We don’t know the extent to which tamarind was used in the preparations of these meats, or whether they played a part in how we make today’s rasam and kuzhambu.

We do know that lentils or dals, the base of such a kuzhambu, do not make an appearance in most Tamil works from the Sangam period.

FOOD OF THE KINGS, A HUMBLE BROTH

Food historians and written works across ages have indicated the tamarind broth as a humble pastoral preparation, as well as a “food of the kings”.

Works from the period indicate pastoral folk imbibed an aromatic tamarind soup, or suupa, in their diets - akin to today’s rasam, according to the 1967 The Classical Age of the Tamils, by M. Arokiasami.

Centuries earlier, in 1699 AD, Keladi Basavaraja, the scholarly king of Keladi who ruled from 1694 to 1714 AD, writes in elaborate detail in his Sanskrit encyclopaedic work Sivatattvaratnakara, on a range of topics, from governance, religion and the types of perfumes royals indulge in, to food, kitchen utensils, recipes and the qualities of a good cook.

The Keladi dynasty, initially a vassal of the great Vijayanagar empire, ruled significant parts of southwestern India comprising of present-day Karnataka and parts of northern Kerala.

King Basavaraja is said to have written this book, which has some 30,000 verses, in response to his son’s request to “learn all knowledge” (sarvavidya).

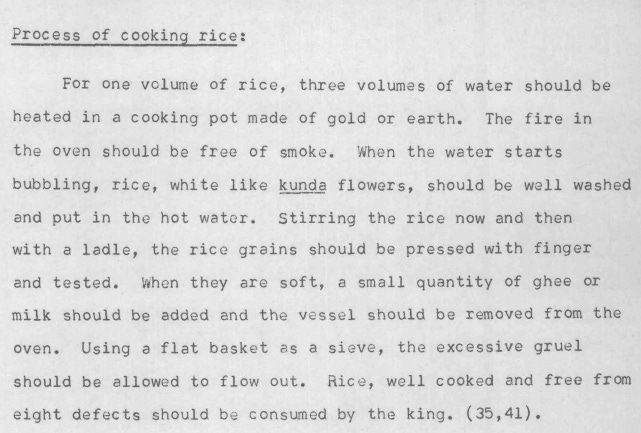

In an extensive chapter on food, the king describes the utensils used in the royal kitchen, the qualities a good cook must possess, how pickles, vegetables and pulses are prepared, and a detailed recipe for making the perfect boiled rice.

This is where we find another mention of our tamarind broth - “Tamarind, cooked in oil with a dash of hingu (asafoetida), is recommended to be poured over rice as a finish.”

These are but snippets from our past, and there may be several more mentions of a tamarind-based broth both in written texts and oral family histories, that evolved into the present-day rasam or kuzhambu (sambar has a parallel tale of Maratha origin).

But, the stories around what goes into that Sunday kuzhambu, tales of a royal feast and a peasant’s meal, of the hero ingredient traveling continents and becoming an Indian staple, these make the food we eat, and our memories, tastier.

Author’s note: The information in this article is based on translations of original works, free online resources, and family recipes. Do hit me up with any more information, point out discrepancies, but especially, with your own versions of this recipe.

A humble tamarind broth

This is a tale of a hero ingredient that traveled continents thousands of years ago, became part of both a royal feast and a peasant meal, and evolved into an Indian kitchen staple