Spilling the tea: the delight of gossiping

Gossiping creates spaces for us to speak our truth, measure our morals and judge our actions against those of the people we’re gossiping about. “Would I do the same?”

My favourite commute pass-time this past month has been listening to banal gossip about people I don’t know and will likely never meet. I heard a story about a high-end dog salon where groomers fought over expensive shampoo bottles; was excited and crushed by the twists in a tale about bitchy moms of high-school girls; I cringed at the utter stupidity of teenagers, then realised I was cringing because I was that teenager!

These stories are from the podcast Normal Gossip by Defector Media. Its steaming tea is the highlight of my evenings and has very likely replaced the 50-minute bitching sessions with my best friend that otherwise occupied my commute.

Over a month of listening to these one-hour episodes — almost bingeing on them like some true crime show — I began to wonder why this show managed to hold my attention where so many others had failed, and why I was deriving such pure, voyeuristic pleasure from the stories of people I don’t know.

It got me thinking about gossip and my relationship with it — a question the show’s host Kelsey McKinney asks her guests before she dives into the juicy details.

McKinney admits to being an "insufferable gossip" in an NYT Op-Ed. Titled Gossip is Not a Sin, she writes about grappling with her conservative Christian upbringing that demonised gossiping while loving the act of gossiping because of its capacity to entertain, improve bonding and even break down toxic structures (#MeToo).

I, on the other hand, have never been restricted by upbringing or culture. Gossiping is second nature to most Indian households. My earliest memory of my relationship with gossip goes back to when I was just entering my teens. I’d walk back from school, change out of my uniform and settle down on the kitchen slab, while my Amma would make hot dosas. As we gulped them down, I would gossip with her about my day and let out all my teenage angst about being the fat girl and friend-zoned, bitching about the popular girl (often stemming from a place of insecurity) or feeling unappreciated by teachers.

“Amma, why don’t boys look at me like they do at her?” And “Amma, did so-and-so’s dad pay more money to make him a school captain?”

And Amma would help me feel normal about it all by telling me a story from her college and school days. About the popular girl she never liked, the best friend who had her back, or starting a fight with boys on a public bus.

Many days, we would go further back into history, to the 1920s and 1930s. Family history that my mother only knew because of gossiping with her mother and grandmother. Property and money, unfairness and injustice, love and kindness. Of lives lived and lives lost.

Her stories took me to a world I didn't know but would show me that it’s okay to be insecure, and that eventually we all find our way and carve our paths.

When I left for college, my younger brother took my place and would dangle it as some prized possession - “haha, I gossiped with Amma and you can’t! Who told you to go?”

Through my twenties and now thirties, my gossip circle has always been small - Amma, my best friend from college, and over the past 5 years, my husband. The point of the gossip is different with each of them, but the gossiping endures; its effect on the mind and heart is the same. It’s relief, it allows one to let off steam and form deep bonds. For me, in my small circle, it’s a safe space to be bitchy without being judged, to process and deal with day-to-day frustrations and then go back to behaving well.

Of course, gossip can be malicious and that kind can cause harm beyond repair to the persons being gossiped about. It can break up communities, and make strangers out of neighbours. It can, quite simply, be cruel.

But that kind of gossip is rare, according to a 2019 study that McKinney refers to in that NYT piece.

Most gossip is really just about fulfilling an innate and deeply human need to story-tell and imagine what it’s like in someone else’s world. It creates spaces for us to speak our truth, measure our morals and judge our actions against those of the people we’re gossiping about. “Would I do the same?”

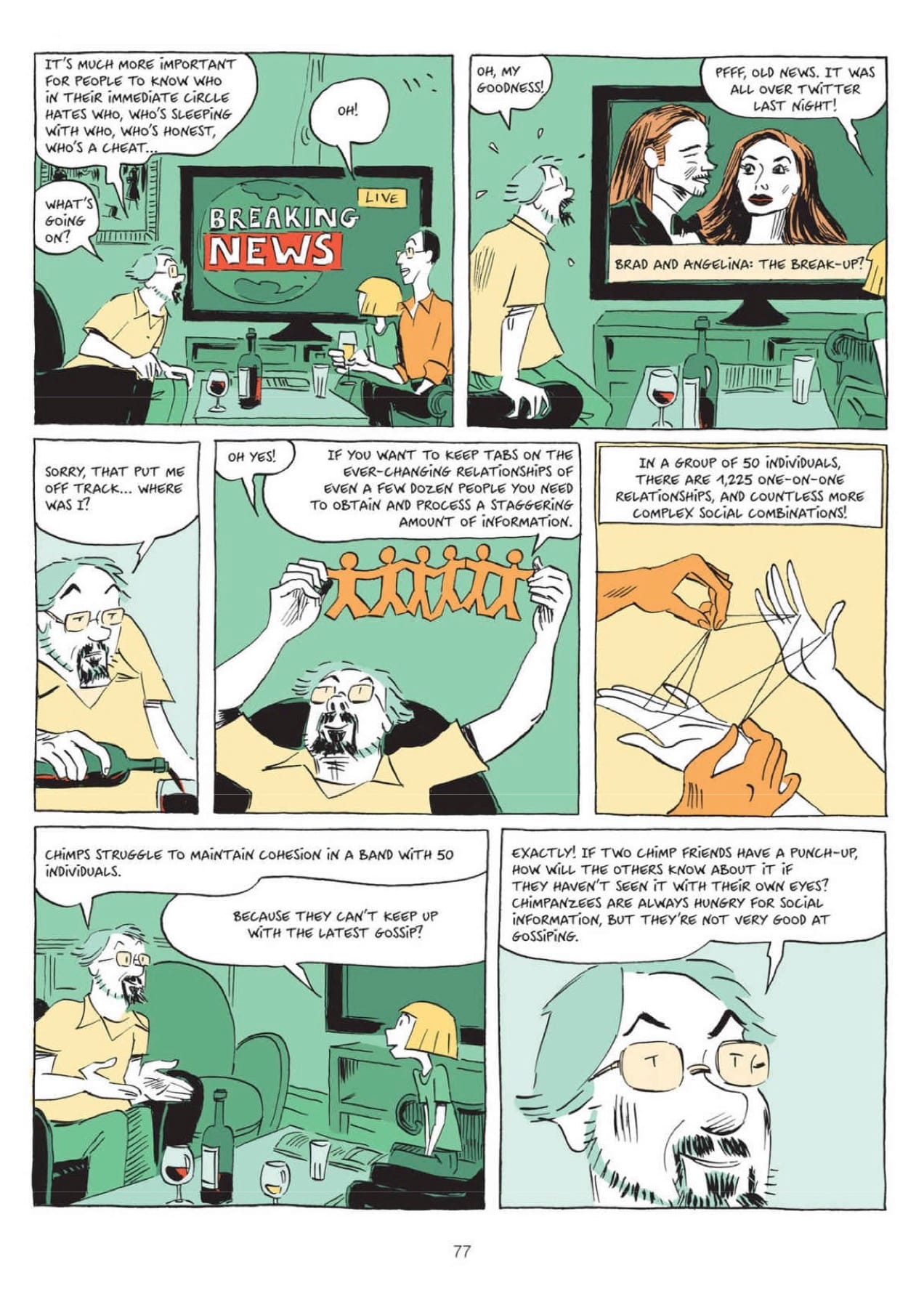

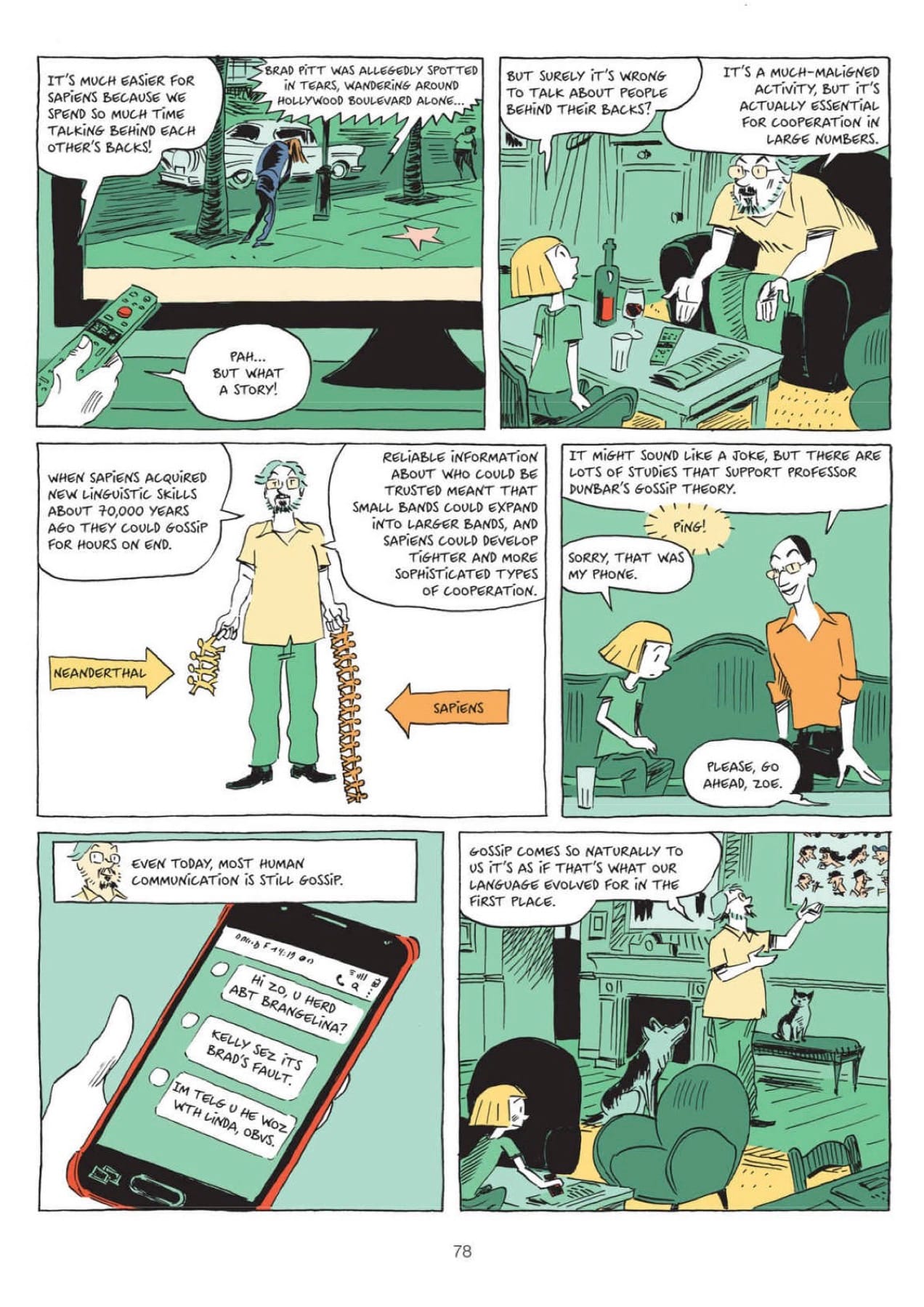

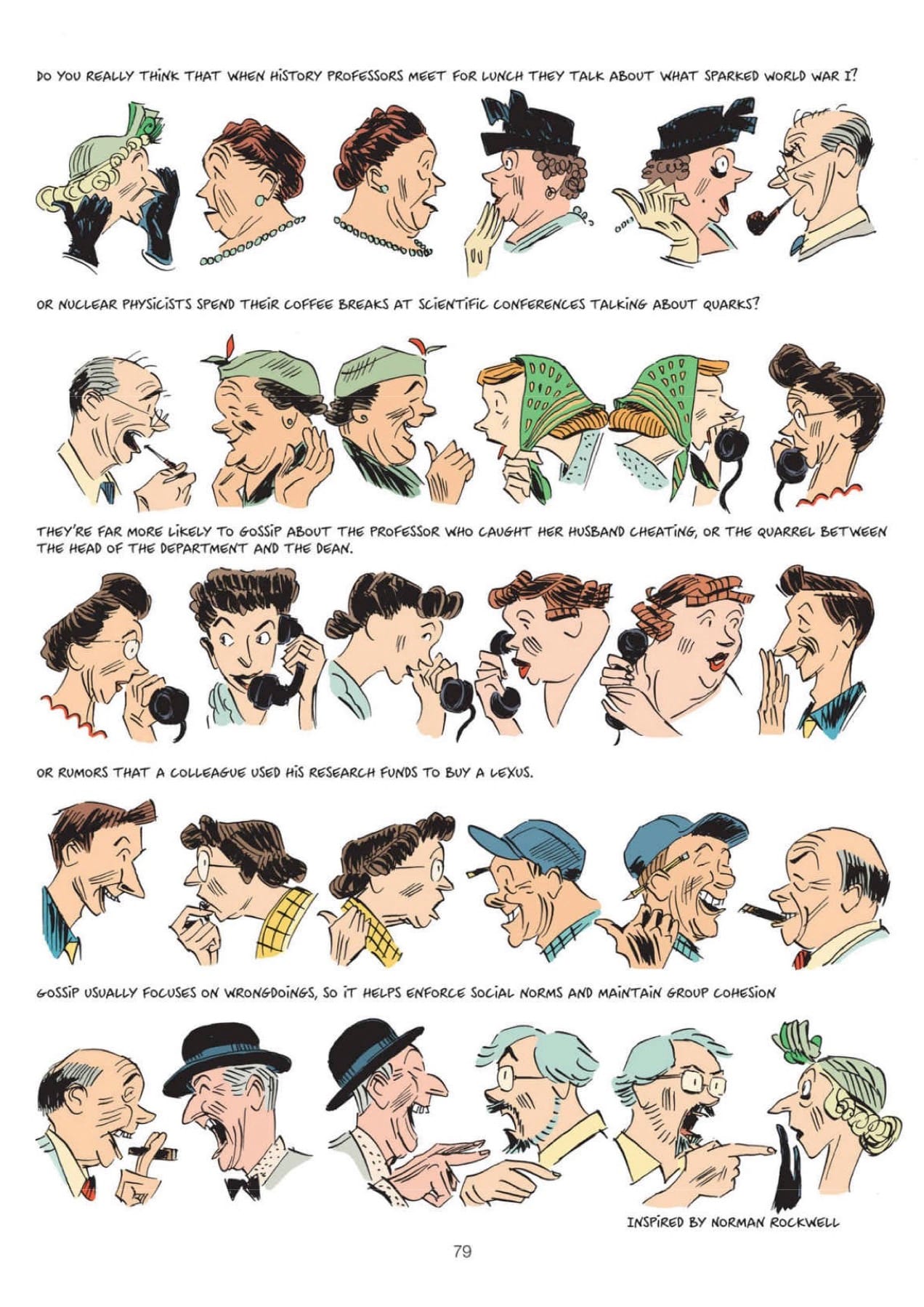

Yuval Noah Harari, in his seminal book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, cites Robin Dunbar's Gossip theory and says that while gossip is a much-maligned activity, it is essential for cooperation. It comes so naturally to humans, it's as though that's what language evolved for.

Excerpts from the graphic novel version of Harari's book

That’s perhaps why Normal Gossip is so popular. The makers say their popularity is all organic, by word-of-mouth — or gossip if you will. It’s also perhaps why the Reddits and Threads and Twitters of the world thrive.

Gossiping is an essential human language. And that’s probably what makes it so endearing.